A lake that was once one of the largest bodies of freshwater in the entire nation disappeared around 130 ago, thanks to greedy colonialists draining its waters for farming purposes.

But last year, that lake suddenly reemerged. Its reappearance brought joyous news… but also some painful impacts. Learn more about the intriguing Tulare Lake.

Tulare Lake’s History

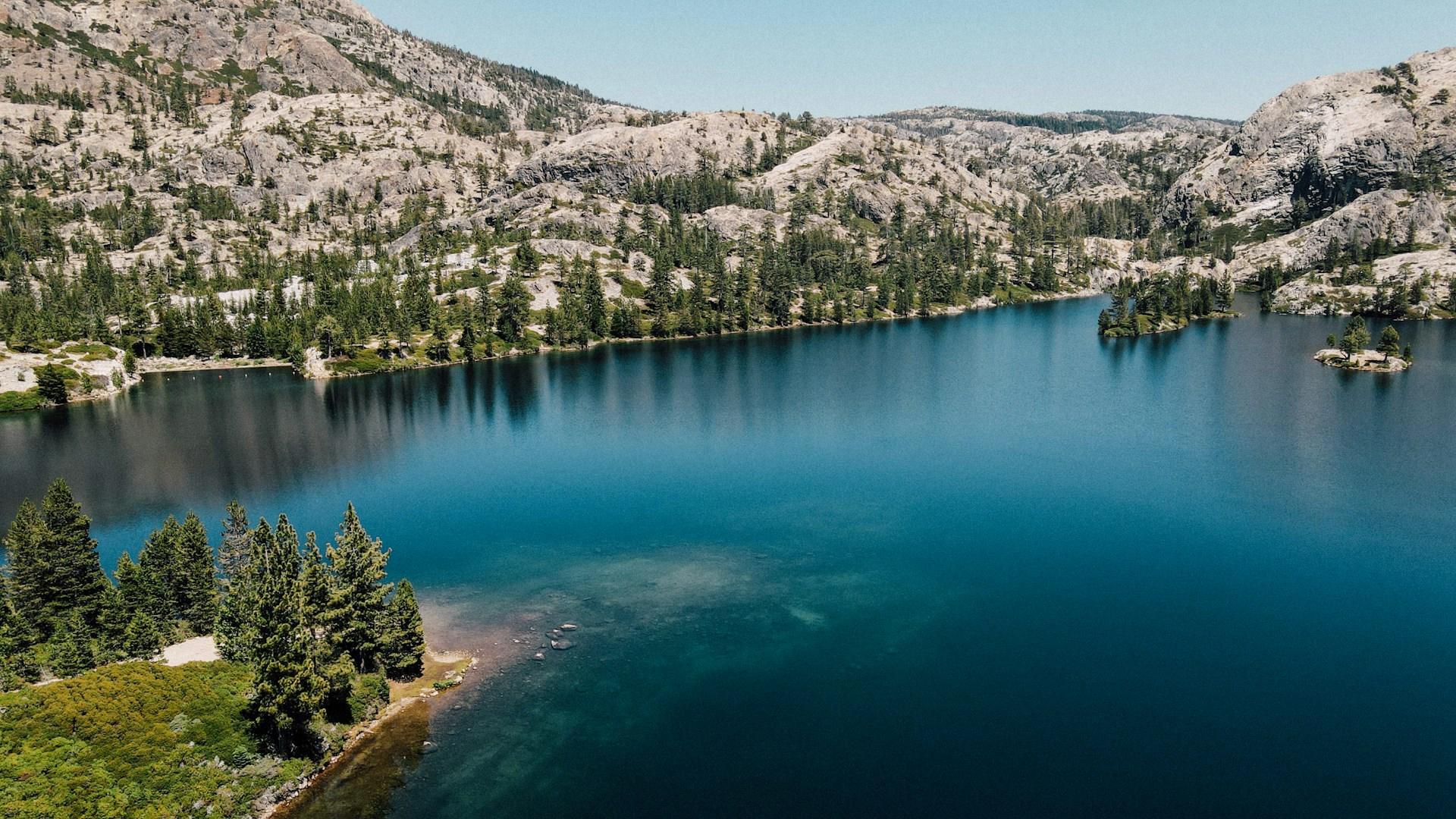

The Tulare Lake was located in California’s San Joaquin Valley. In the late 19th century, the lake stretched more than 100 miles long and 30 miles wide.

Vivian Underhill of Northeastern University said it was “the largest body of freshwater west of the Mississippi River.” In this period, it contained so much water that a steamship passing through could carry “agricultural supplies from the Bakersfield area up to Fresno (at the heart of the San Joaquin Valley” up to San Francisco, covering a 300-mile distance.

Man-Made Irrigation Made It Vanish

In the next few decades, however, the lake and its connecting waterways, which made the aforementioned route possible, disappeared thanks to man-made irrigation.

The lake was “ancestral” to the indigenous Tachi Yokut Tribe. The Tulare lake was named “Pa’ashi” in the tribe’s language. It received its water from melting snow out of the Sierra Nevada mountains, instead of the scant rainfall in the region.

Fresno Was a Lakeside Town

In the present day, the landscape of San Joaquin Valley is arid. Naturally, it might be hard to imagine that in the 1800s, “Fresno was a lakeside town,” said Underhill.

These days, Fresnco receives an average of just over 10 inches of rain annually. Sometimes, it gets as little as three inches, according to the National Weather Service.

Reclamation Practices of the Past

Underhill, who specializes in ethnography and environmental justice, said the lake first began disappearing in the late 1850s and early 1860s. It was all due to “the state of California’s desire to take [historically indigenous] land and put it into private ownership.”

The process, called “reclamation,” which often involved draining inundated land or irrigating land to create lush land for cultivating crops. Basically, if people could drain the land, they would be granted ownership of parts of it.

It Fully Disappeared in the 1890s

“There was a big incentive for white setters to start doing that work,” Underhill added. She described the process as a “deeply settler colonial project.”

When its water was finally all drained and used to irrigate all the dry lands in the area, she continued, the lake fully disappeared for the first time in around 1890. “Now the valley is crisscrossed by hundreds of irrigation canals, all of which were originally built to take that lake water and put it onto irrigated fields.”

The Lake’s Resurrection

But last year, in 2023, Tulare Lake was resurrected, thanks to snow and rain. “California just got inundated with snow in the winter and then rain in the spring,” Underhill said.

With the rain and snow events going on continuously, the snow melted very rapidly. All this ran into the land depression where Tulare Lake once sat.

Return of the Local Wildlife

After Tulare Lake’s resurgence, the local wildlife also returned to thrive. Birds, especially, returned. Pelicans, hawks, and waterbirds came back to the lake. Meanwhile, “the Tachi also say that they’ve seen burrowing owls nesting around the shore,” Underhill added.

Burrowing owls was once described by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as “vulnerable or imperiled” species. Furthermore, fish and amphibians, likely carried over by rainfall and flooding, also came home.

Impact on Humans

For the indigenous tribe of Tachi Yokuts, the lake’s return was “just an incredibly powerful and spiritual experience. They’ve been holding ceremonies on the side of the lake. They’ve been able to practice their traditional hunting and fishing practices again,” Underhill said.

However, for the farmworkers and landowners in San Joaquin Valley, their experiences have been different and a lot more painful.

Devastating Losses in Agriculture

As a result of the flooding, many people lost their homes entirely. Many agricultural workers also suffered devastating losses in their industry.

There’s now an effort to once again drain the lake; Underhill said she expected it to remain in some form for about two more years. But new atmospheric river events in California this year may complicate their efforts.

The Lake Wants to Stay

“Under climate change, floods of this magnitude or higher will happen with increasing frequency,” Underhill said.

“At a certain point, I think it would behoove the State of California to realize that Tulare Lake wants to remain. And in fact, there’s a lot of economic benefit that could be gained from letting it remain.”

Not a Flood, but a Lake Returning

Underhill is keen to point out that this flooding of the area is not actually a flood. “This is a lake returning,” she emphasized. She also pointed out that the lake’s already tried to return several times in the past — in the ‘30s, ‘60s, and ‘80s.

If we look at the broader environmental context, Underhill said, “This landscape has always been one of lakes and wetlands. And our current irrigated agriculture is just a century-long blip in this larger geologic history.” Nature, it seems, can be stronger than humanity.